Feb. 26, 2021

Why Canada should invest in ‘macrogrids’ for greener, more reliable electricity

As the recent disaster in Texas showed, climate change requires electricity utilities to prepare for extreme events. This “global weirding” leads to more intense storms, higher wind speeds, heatwaves and droughts that can threaten the performance of electricity systems.

The electricity sector must adapt to this changing climate while also playing a central role in mitigating climate change. Greenhouse gas emissions can be reduced a number of ways, but the electricity sector is expected to play a central role in decarbonization. Zero-emissions electricity can be used to electrify transportation, heating and industry and help achieve emissions reduction in these sectors.

- Co-authors of this article with Blake Shaffer and G. Kent Fellows are Brett Dolter, University of Regina and Nicholas Rivers, University of Ottawa

Enhancing long-distance transmission is viewed as a cost-effective way to enable a clean and reliable power grid, and to lower the cost of meeting our climate targets. Now is the time to strengthen transmission links in Canada.

Insurance for climate extremes

An early lesson from the Texas power outages is that extreme conditions can lead to failures across all forms of power supply. The state lost the capacity to generate electricity from natural gas, coal, nuclear and wind simultaneously. But it also lacked transmission connections to other electricity systems that could have bolstered supply.

Long-distance transmission offers the opportunity to escape the correlative clutch of extreme weather, by accessing energy and spare capacity in areas not beset by the same weather patterns. For example, while Texas was in its deep freeze, relatively balmy conditions in California meant there was a surplus of electricity generation capability in that region — but no means to get it to Texas. Building new transmission lines and connections across broader regions can act as an insurance policy, providing a back-up for regions hit by the crippling effects of climate change.

The 1998 Quebec ice storm left 3.5 million Quebecers and a million Ontarians, as well as thousands in New Brunswick, without power.

Robert Galbraith, Canadian Press

Transmission is also vulnerable to climate disruptions, such as crippling ice storms that leave wires temporarily inoperable. This may mean using stronger poles when building transmission, or burying major high-voltage transmission links.

In any event, more transmission links between regions can improve resilience by co-ordinating supply across larger regions. Well-connected grids that are larger than the areas disrupted by weather systems can be more resilient to climate extremes.

Lowering the cost of clean power

Adding more transmission can also play a role in mitigating climate change. Numerous studies have found that building a larger transmission grid allows for greater shares of renewables onto the grid, ultimately lowering the overall cost of electricity.

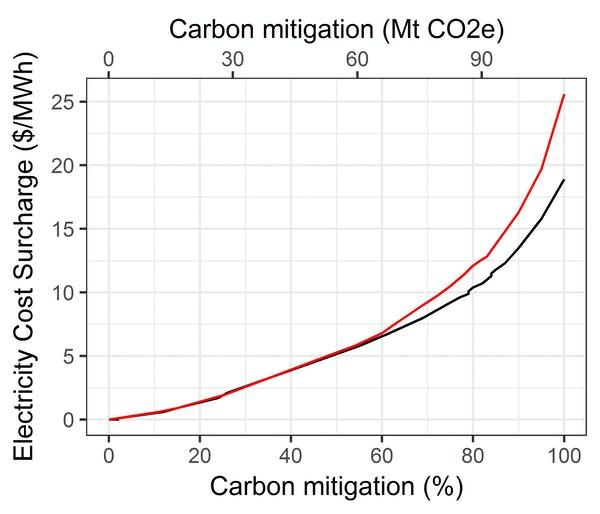

In a recent study, two of us looked at the role transmission could play in lowering greenhouse gas emissions in Canada’s electricity sector. We found the cost of reducing greenhouse gas emissions is lower when new or enhanced transmission links can be built between provinces.

Average cost increase to electricity in Canada at different levels of decarbonization, with new transmission (black) and without new transmission (red). New transmission lowers the cost of reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

Graphic provided by the authors

Much of the value of transmission in these scenarios comes from linking high-quality wind and solar resources with flexible zero-emission generation that can produce electricity on demand. In Canada, our system is dominated by hydroelectricity, but most of this hydro capacity is located in five provinces: British Columbia, Manitoba, Ontario, Québec and Newfoundland and Labrador.

In the west, Alberta and Saskatchewan are great locations for building low-cost wind and solar farms. Enhanced interprovincial transmission would allow Alberta and Saskatchewan to build more variable wind and solar, with the assurance that they could receive backup power from B.C. and Manitoba when the wind isn’t blowing and the sun isn’t shining.

When wind and solar are plentiful, the flow of low-cost energy can reverse to allow B.C. and Manitoba the opportunity to better manage their hydro reservoir levels. Provinces can only benefit from trading with each other if we have the infrastructure to make that trade possible.

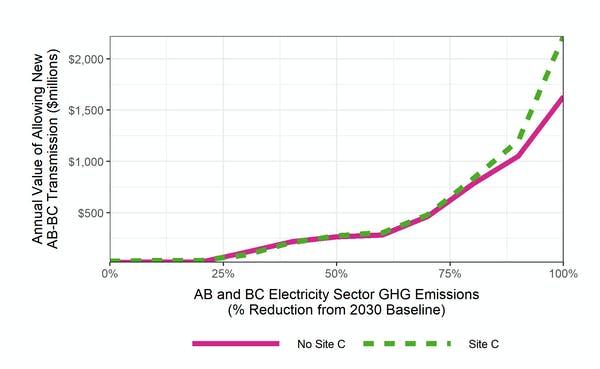

A recent working paper examined the role that new transmission links could play in decarbonizing the B.C. and Alberta electricity systems. We again found that enabling greater electricity trade between B.C. and Alberta can reduce the cost of deep cuts to greenhouse gas emissions by billions of dollars a year. Although we focused on the value of the Site C project, the analysis showed that new transmission would offer benefits of much greater value than a single hydroelectric project.

The value of enabling new transmission links between Alberta and B.C. as greenhouse gas emissions reductions are pursued.

Graphic provided by the authors

Getting transmission built

With the benefits that enhanced electricity transmission links can provide, one might think new projects would be a slam dunk. But there are barriers to getting projects built.

First, electricity grids in Canada are managed at the provincial level, most often by Crown corporations. Decisions by the Crowns are influenced not simply by economics, but also by political considerations. If a transmission project enables greater imports of electricity to Saskatchewan from Manitoba, it raises a flag about lost economic development opportunity within Saskatchewan. Successful transmission agreements need to ensure a two-way flow of benefits.

Second, transmission can be expensive. On this front, the Canadian government could open up the purse strings to fund new transmission links between provinces. It has already shown a willingness to do so.

Lastly, transmission lines are long linear projects, not unlike pipelines. Siting transmission lines can be contentious, even when they are delivering zero-emissions electricity. Using infrastructure corridors, such as existing railway right of ways or the proposed Canadian Northern Corridor, could help better facilitate co-operation between regions and reduce the risks of siting transmission lines.

If Canada can address these barriers to transmission, we should find ourselves in an advantageous position, where we are more resilient to climate extremes and have achieved a lower-cost, zero-emissions electricity grid.

Blake Shaffer is an assistant professor in the Department of Economics and The School of Public Policy.

G. Kent Fellows is a research associate and the associate program director of the Canadian Northern Corridor research program at The School of Public Policy