June 28, 2022

UCalgary prof's book talks of buildings that welcomed, directed, controlled and rejected immigrants

While on a research trip in Montreal to work out ideas for a book, UCalgary scholar David Monteyne happened upon an abandoned four-storey building near Windsor Station. The word “Immigration,” etched into a stone lintel, offered the only clue to its previous purpose.

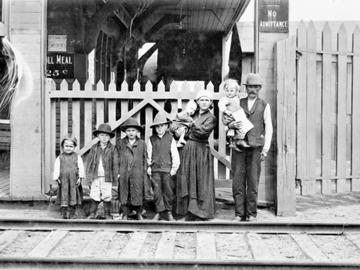

- Photo above, Illustration 5.22: Thirty-nine Sikh men were held in the Victoria immigrant detention hospital in 1913. Here the men are shown in the background lining the outdoor staircase behind security screening, while their supporters pose outside the perimeter fence.

Though he did not yet know it, this accidental discovery would prove foundational to Monteyne’s book about Canadian immigration architecture. While consulting various archival sources, Dr. Monteyne, PhD, an associate professor in the School of Architecture, Planning and Landscape, kept coming across different kinds of immigrant narratives about reception buildings and how they were used. When he learned that a whole network of buildings had existed throughout Canada to accommodate, detain or incarcerate immigrants, the pieces began to fall into place.

David Monteyne

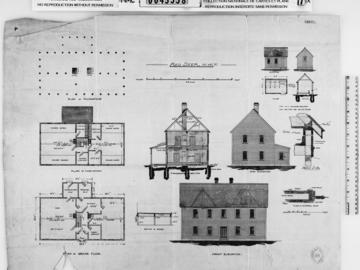

“I was able to use immigrant memoirs — written in the first person by people going through these immigration buildings — in conjunction with documents from the national archives,” Monteyne explains. “With the original architectural drawings, I could describe those spaces and how people interacted with them.”

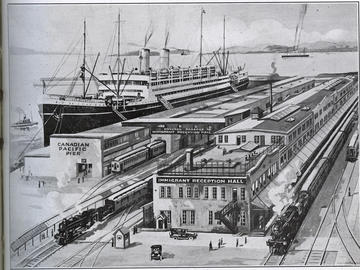

For the Temporary Accommodation of Settlers: Architecture and Immigrant Reception in Canada, 1870-1930 was published in December by McGill-Queen’s University Press. The book examines the network of nearly 60 immigration buildings through the lens of cultural landscape studies — looking at social history within built spaces.

Major architectural history groups take note

The book quickly caught the attention of two major architectural history organizations for their annual prizes. In May, Monteyne flew to San Antonio to receive the Abbott Lowell Cummings Award, given annually by the Vernacular Architectural Forum to the “newly published book that has made the most significant contribution to the study of vernacular architecture and cultural landscapes of North America.”

Then, he also received the John Brinckerhoff Jackson Book Award from the University of Virginia’s Center for Cultural Landscapes, which is given to recent landscape studies that break new ground in method or interpretation.

Martha J. McNamara, Cummings Award committee chair, notes that “Monteyne’s study of Canadian immigration architecture built from 1870 to the mid-1930s and the spatial practices it shaped, opens up an entirely new way of understanding the lived experience of immigrants drawn to the promise of opportunity in Canada.”

Illustration 5.1 The immigration building that, in many respects, launched the book. Former immigrant detention hospital, Montreal. Built in 1914, demolished in 2015.

Prior to 1902, with few exceptions, immigrants were highly encouraged to come to Canada. But as the number of immigrants increased, policy and procedures shifted to assess immigrants’ potential “for economic productivity and good citizenship.” This resulted in additional spaces for immigrant selection and rejection. It’s a familiar condition, even in our 21st century context, where the detention and deportation of immigrants continue to occupy space in political discourse and news headlines.

For the Temporary Accommodation of Settlers reminds us that “the built environment of immigration both structures a country’s interaction with potential future citizens and signals a country’s ability to show compassion for the wrenching experiences of global migrants,” concludes McNamara.

Perspective of cultural landscapes enhances relevance

Monteyne’s decision to focus on immigration buildings from the perspective of cultural landscapes rather than purely architectural history has made the book relevant and interesting to a broader audience than just architects and architectural historians.

A significant number of people living in Canada are immigrants or have claim to a parent or grandparent who emigrated to Canada. This book helps to paint a picture of what it would have been like for our grandparents and great-grandparents to be newly arrived in Canada.

“In Canada we don’t have that one iconic building, like Ellis Island, so I recreated the kinds of buildings that people went through in the early period of immigration,” Monteyne explains. He also gave a voice to the people in those buildings, which added a unique dimension to the book.

“Not much architectural history has been able to talk about individual users. Historically, that information is not typically recorded.”

After years of research and writing, Monteyne is gratified by the book’s success. “It shows you that you’re doing something right,” he reflects. A major book award “gives you a profile, which is not easy when you’re in a place like Calgary, somewhat out of the main networks of architectural historians.”