Dec. 21, 2020

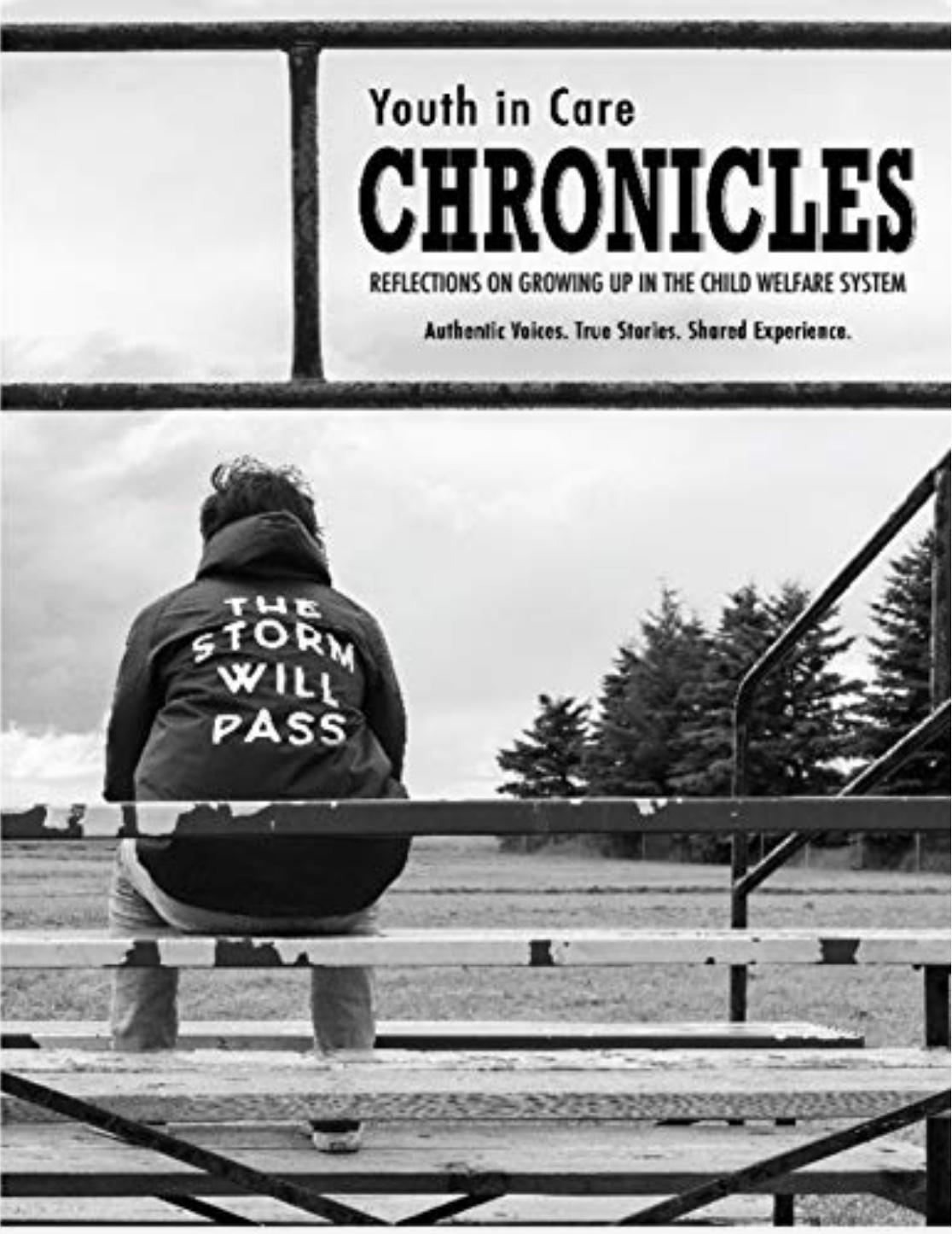

Inspirational book provides hope for youth in Alberta's child-care system

For young Cody Murrell, Christmas was most certainly not “the most wonderful time of the year.”

As a child in Alberta’s youth-in-care system, Christmas was when the differences between himself and others were most starkly underlined. Christmas was when most of the other kids in the group home disappeared.

“There were several Christmases that I spent alone in that group home,” says Murrell. “The other kids were with their families. Sometimes there might have been one or two kids, and you just knew that you were different. It was one of those things that made you feel like a kid who lives in care. You just know you’re different.”

Making things a little less “different” for kids in care is a big part of why Murrell and 17 other people who grew up in Alberta’s child welfare system are sharing their life stories in a new book called Youth in Care Chronicles: Reflections on Growing Up in the Child Welfare System.

Murrell, who graduated with a Bachelor of Social Work (with a 4.0 GPA) in 2016 from the faculty’s Edmonton campus, has come full circle in a way. He’s now a supervisor with Alberta Children’s Services and he says he hopes the new book will bring awareness and reframe societal narratives around youth in care.

“There's often a lot of shame that you experience,” says Murrell. “There's a lot of stigma that actually keeps people from openly sharing their experiences. And it internalizes guilt for them and makes them feel bad. I have friends that I grew up with in care, who would not tell anyone. They'll make up these elaborate stories about their family to avoid actually just saying, 'Oh, no, I grew up in care.' Because they're so embarrassed and they're worried about what that will mean and how they'll be treated.

"So, I hope this book helps change some societal narratives. I hope it also helps youth who are growing up in care to not be afraid and know that it's okay to be vulnerable.”

Changing the narrative about kids in care

Like many of the other authors in the book, Murrell overcame unimaginable odds and hardships in his life. His father was in and out of prison and died shortly after Murrell turned five years old. His mother sank into a depression and began to use heavy drugs, working to support her family with sex work, before social services intervened.

From there it was a steady procession of foster parents and group homes for Cody. Not surprisingly he lashed out and “troublemaker” was a permanent addition to his growing list of labels. The cycle continued until somebody actually showed him they cared.

It was the mother of one of his high school friends who took an interest in him and began to nurture him. She cared about doing little and big things like taking him to rugby or football practice and teaching him, as he says, what it means to be part of a family — no matter how hard he tried to push her away.

“In my whole life, I've had hundreds and hundreds of caregivers — between foster parents and group-care staff,” says Murrell, “So it really does warp your view of what relationships are and what they should be. You learn, 'Hey, if you're difficult enough, people get rid of you,' and it reinforces the idea that no one wants you, or a relationship with you.

"I hope people really hear the difference my adopted family made. They had no need to, and at times I certainly did do things to push them away. But they stuck at it, and it has been what has changed my life.”

I'm really hoping that this book will show [youth-in-care] 'Hey, there are a lot of really crazy, insane, difficult stories and challenges that everyone went through, but keep going through it. You can get through it and you can be successful.

A message of hope

The book’s message of hope for youth in care and understanding in the community is a matter of life and death. Youth in care are 200 times more likely to become homeless, 60 times more likely to be victims of sex trafficking, five times more likely to die young and are much more likely to experience poor physical and mental health outcomes.

The project, which was funded by the CanFASD Research Network, was compiled by a diverse editorial team that included Murrell and two other former youth in care who are now child welfare supervisors (Theresa Tucker Wright and Megan Mierau), a recent graduate of the UCalgary social work program in Calgary (Erin Leveque), Dr. Dorothy Badry, PhD, RSW from the Faculty of Social Work, and Penny Frazier, a freelance writer who has worked with marginalized youth for over four decades.

Murrell hopes that many people will read the book — which is available in paperback and online on Amazon — and spread its message of hope during the Christmas season. He reflects on when he was 12 and saw no possibility of a better future. He says he had “given up at life,” and when a social worker asked him what he wanted to be when he grew up, he looked at her dumbfounded, saying, “Well, I’m going to live on welfare.”

In many ways he and the other authors embarked on this project as a message of hope to their former selves — the children who will find themselves in similar dark places. Alone in group homes across Alberta during Christmas.

“I hope it does provide inspiration,” says Murrell. “When I was growing up in care, I didn't know a single youth in care who had successfully gotten a job and maintained it for more than a year. The bar was really low. I'm really hoping that this book will show [youth in care] 'Hey, there are a lot of really crazy, insane, difficult stories and challenges that everyone went through, but keep going through it. You can get through it and you can be successful. Know that that is an option.”

Media availability

Contributors to the book and members of the editorial team are available for interview from across the province. Please contact Megan Mierau or Penny Frazier to arrange in-person interviews in Edmonton, Calgary or Lethbridge.

Megan Mierau: meganashleymierau@gmail.com

Penny Frazier: penny@pennyfrazier.ca