June 19, 2018

Groundwater flooding, not sewer backup, blamed for damaging homes along Elbow River in 2013

Groundwater flooding from the Elbow River — as opposed to river flooding overland — caused significant damage to Calgary homes during the disastrous June 2013 flood, University of Calgary researchers say.

In many homes in the hardest-hit communities of Elbow Park, Rideau, and Roxboro in southwest Calgary, groundwater flooding — which occurs when the water table rises up — was misidentified as sewer backup and insurance claims inappropriately paid out on that basis, says a study led by Jason Abboud, now a graduate student in the Department of Geoscience in the Faculty of Science.

“Groundwater flooding happens, and it can happen in the absence of surface water, or overland, flooding. Groundwater flooding can happen sooner, it can manifest as wastewater backup, and it can cause considerable damage,” Abboud, above, says. “If people knew more about this, they would maybe think twice about living on the floodplain.”

Abboud’s study, done as an undergraduate student project, was co-supervised by Dr. Cathy Ryan, PhD, and Dr. G. D. (Jerry) Osborn, PhD, both professors of geoscience at UCalgary. The study included door-to-door and online surveys, conducted a year after the 2013 flood, of residents in 189 homes along the Elbow River.

In homes where the initial route of floodwater entry was known, 88 per cent were initially flooded by groundwater. Twelve per cent reported exclusively groundwater flooding, with no overland flooding.

The cost to repair damage caused by basement flooding alone — which averaged about $96,000 per home — contributed to about half the damage repair cost due to combined overland and basement flooding, based on the homes’ total assessed value, the study found.

Calgary sits atop a river-connected alluvial aquifer of permeable gravel and sand deposits. As the Elbow River rose, so did the subsurface water table.

“Simple groundwater modelling results demonstrated that higher water tables from rivine flood-wave propagation through the aquifer could account for much of the flooding seen in the homes in the communities along the Elbow River,” Abboud says.

The rising groundwater infiltrated aging, cracked sewage collection pipes beneath the three communities. When the water table rose to a level above basement floors, groundwater mixed with sewage entered the homes through basement floor drains, toilets, showers and sinks. True sewer backup, on the other hand, can occur in the absence of groundwater flooding when sewage is prevented from flowing under gravity through the wastewater collection system.

“Although groundwater entry via the wastewater collection system was the most common method floodwater entered homes, groundwater flooding was completely unrecognized by insurance companies,” Abboud says.

The study, “Groundwater Flooding in a River-Connected Alluvial Aquifer” is published in the peer-reviewed Journal of Flood Risk Management.

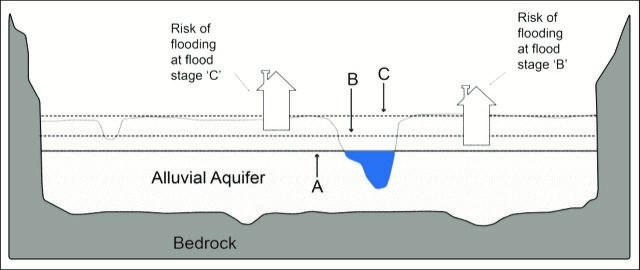

The schematic cross section below depicts homes built in the highly permeable alluvial aquifer, or the river-deposited sediments. At ‘normal’ or base flow conditions, where river level is shown as ‘A', the homes are not susceptible to flooding. However, as the river stage rises, the water table in the alluvial aquifer also rises. Houses with deep basements (house on the right) will experience groundwater flooding when river stage is at ‘B’. Further rise in river stage, shown with ‘C’, would lead to flooding of homes with shallow basements, as seen on the right. This may all happen before the river actually breaches overland banks.

A schematic cross section of homes built in the highly permeable alluvial aquifer.

Groundwater monitoring network needed

Total damages in Alberta from the June 2013 flood exceeded $6 billion, with insurable damages near $2 billion. It was one of the largest payouts in Canadian history. Yet five years after the flood, the groundwater flooding hazard is still not identified on government flood risk maps, monitored for in a systematic way, or recognized by insurance companies.

There was no network — and there still isn’t today — of groundwater monitoring wells providing continuous, real-time data in the three southwest Calgary neighbourhoods inundated along the Elbow River. With such a network, “it would be so easy to monitor groundwater table elevations and separate out groundwater flooding from true sewer backup,” Ryan says.

Insurance companies need to recognize groundwater flooding as a hazard and should consider paying for a groundwater monitoring network in Calgary, Ryan says.

But Glenn McGillivray, managing director at the Institute for Catastrophic Loss Reduction in Toronto, says insurance companies are still “wrapping their minds” around insurance for overland flooding, which became available only in February 2015. “There is no talk in the industry about monitoring groundwater.”

Improved protection measures required

A network of groundwater monitoring wells in areas at most risk of flooding along the Bow and Elbow Rivers would enable government to gather data needed to identify the risk zone for groundwater flooding on hazard maps, Osborn says. Abboud’s study, he notes, found that of 19 surveyed homes located outside of the mapped one-in-100-year overland flood zone, 47 per cent were flooded by groundwater. This shows that groundwater flooding reaches beyond mapped overland water-flooded areas.

“If the province and the city want to address the flood hazard, they’re currently ignoring that aspect of the flood hazard,” Osborn says.

In contrast, the town of Canmore has a network of groundwater monitoring wells, data from which was used to enact a bylaw requiring that all homes built near the Bow River have basement floors higher than predicted one-in-100-year flood levels.

Abboud’s study found that the deeper the basement floor in homes along the Elbow River, the more groundwater flooding residents reported.

Frank Frigo, a hydrologist and leader of watershed analysis for The City of Calgary, says the city is well aware of the groundwater flooding risk, including consultant studies that indicate up to 30 to 40 per cent of total damages in a flood could be caused solely by groundwater flooding.

The city maintains a network of groundwater wells to monitor for soil contamination, river contaminants from past industrial sites, and at operating industrial sites, Frigo says. Those wells, coupled with data from geotechnical drilling done during new infrastructure development, provide a general understanding of the groundwater flooding risk.

“The program does need to continue to be expanded, so we have more information to be able to quantify everything.”

The city plans to install some groundwater monitoring wells in the three communities along the Elbow River, “though it’s one of the lower priorities amongst all our total package of work around flood zones and mitigation,” Frigo says.

The researchers say there are several other measures that governments and the insurance industry need to take to reduce the risk of both overland and groundwater flooding, including:

- limiting further development on the floodplain, or implementing a minimum basement floor elevation higher than the one-in-100-year flood level

- identifying, on property titles, where flood risk is to existing homes in the floodplain

- requiring all these homes to have mandatory backwater preventer valves, to prevent groundwater from rising through basement drains

- ensuring that people who now have homes in the floodplain bear a greater proportional cost of the risk, through higher premiums for flood insurance

The study led by Jason Abboud fits within the Faculty of Science’s strategic plan, Curiosity Sparks Discovery, whose goals include providing students with innovative curricula and authentic learning experiences, and playing an integral role in the community. Abboud would like to thank all the residents along the Elbow River who participated in the survey. Any of those residents who would like a copy of his study should email him at jabboud@ucalgary.ca.